Steven Weinberg makes history

History in the making

SCROLL DOWN

Steven Weinberg makes history

History in the making

Studio Work

Click image to view more

“The final piece ... becomes a living record of the hearts and minds embedded in it ...”

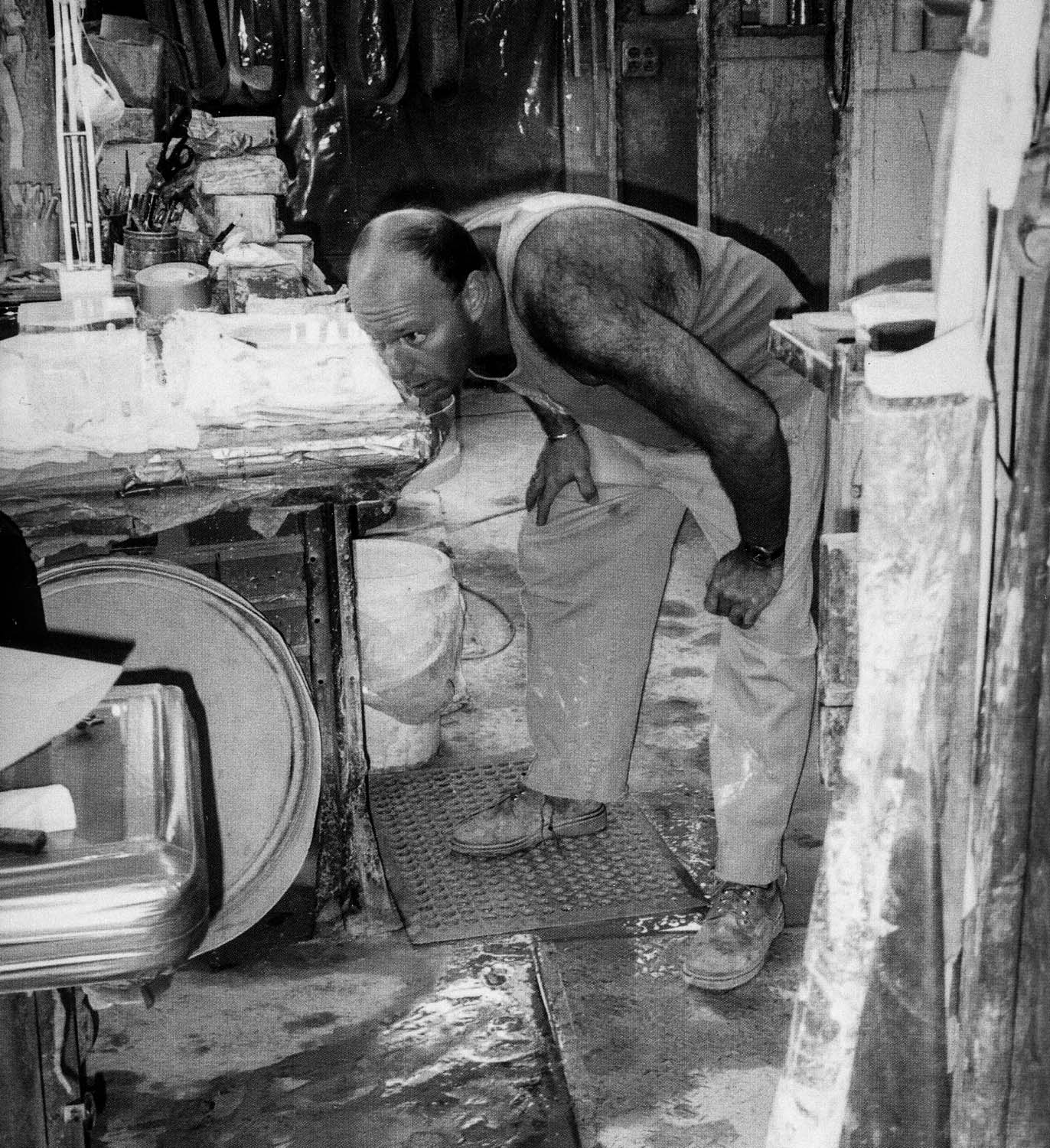

Steven Weinberg in his studio

Studio Life

Studio

Studio Life

Studio

The Studio Life

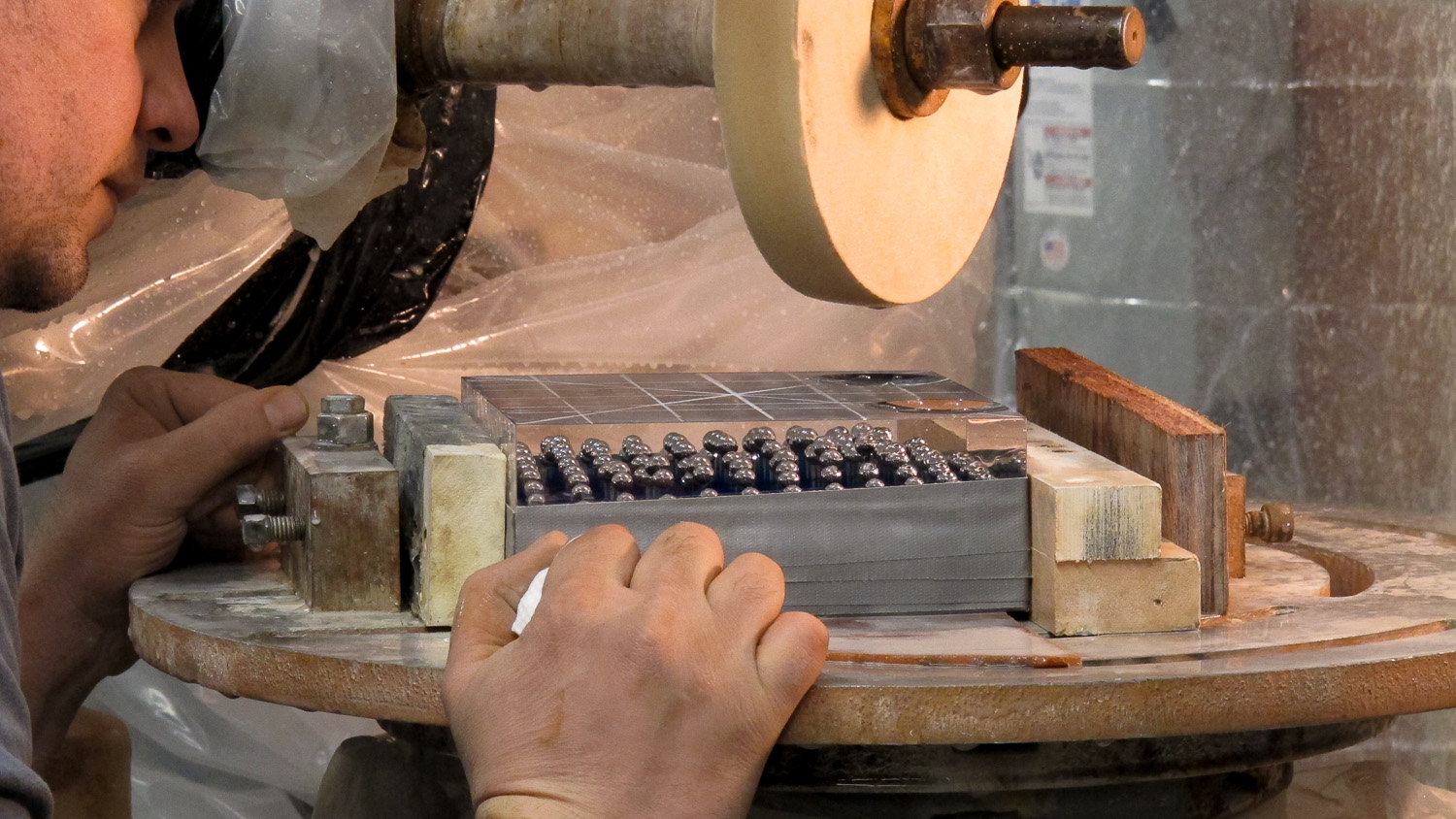

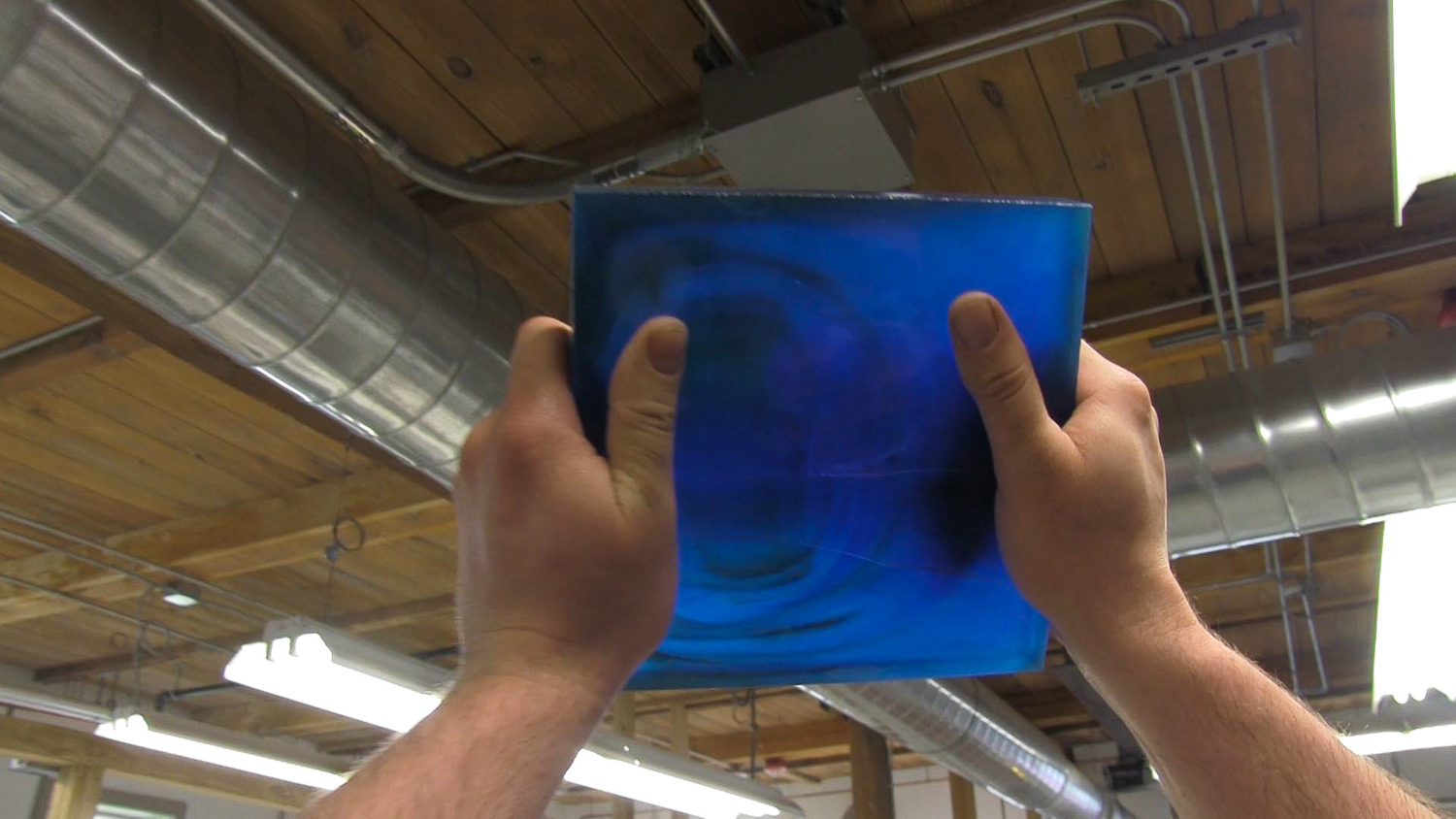

Hand finishing a crystal tile

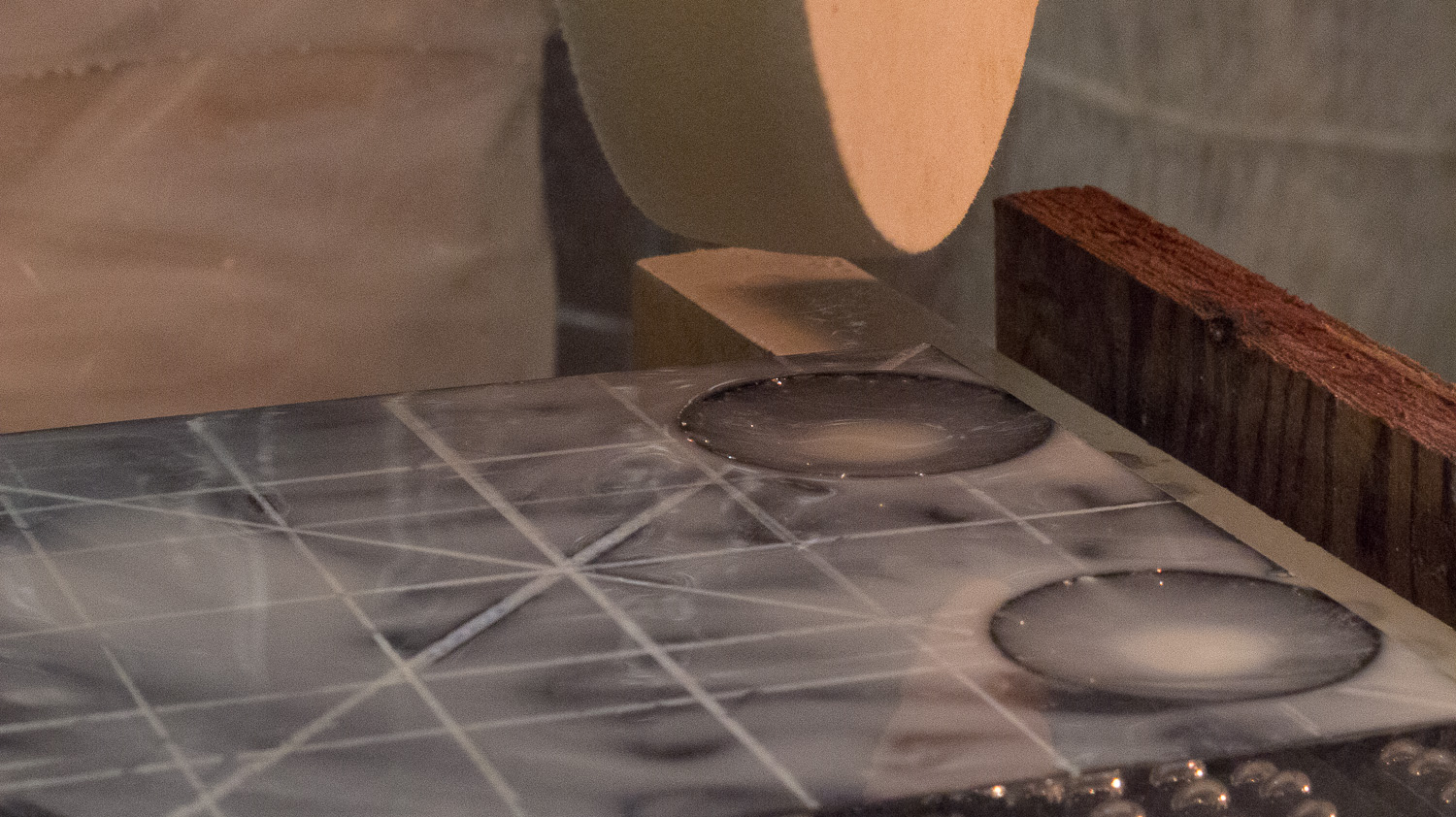

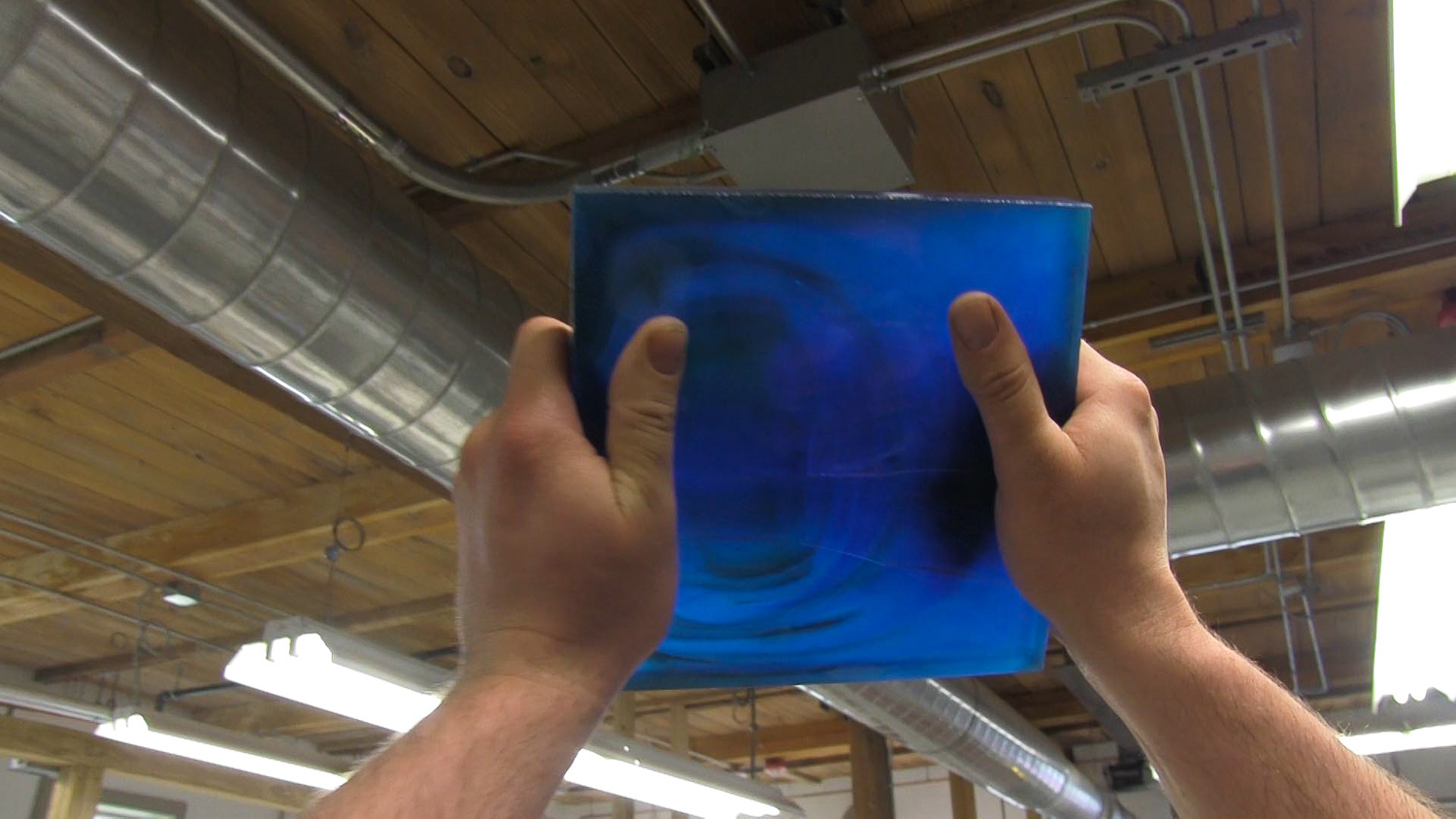

Crystal Universe

Crystal Universe

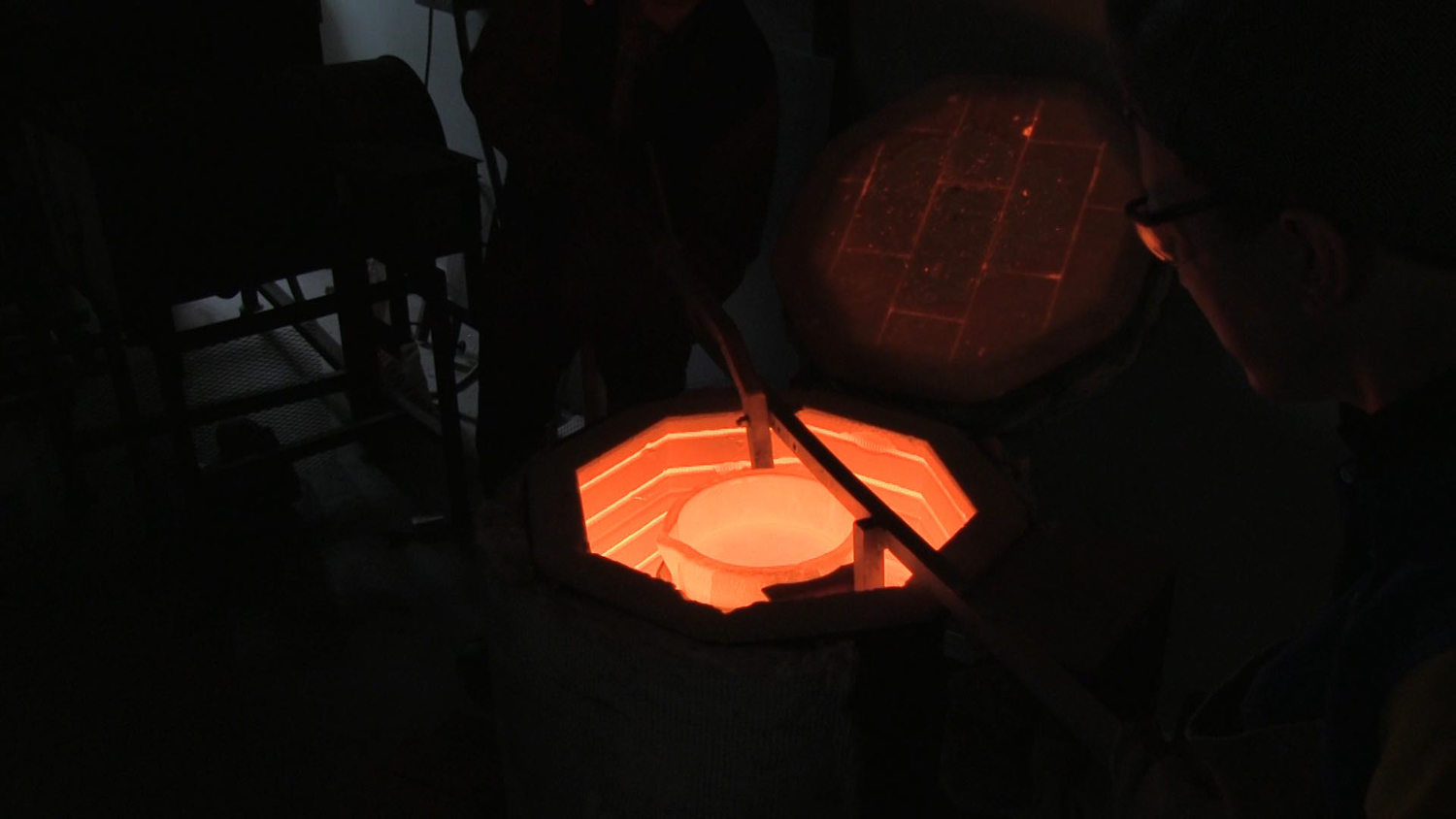

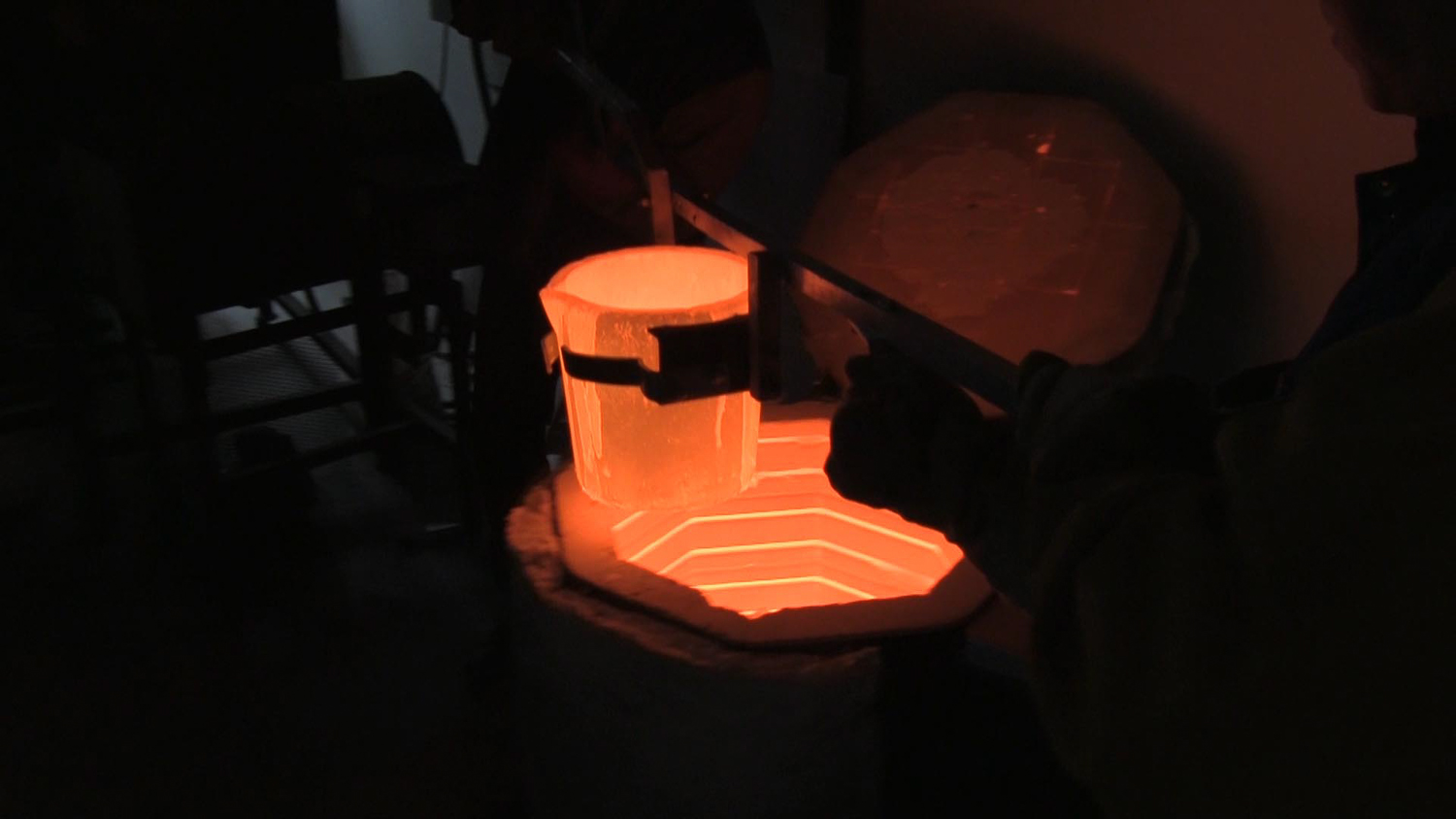

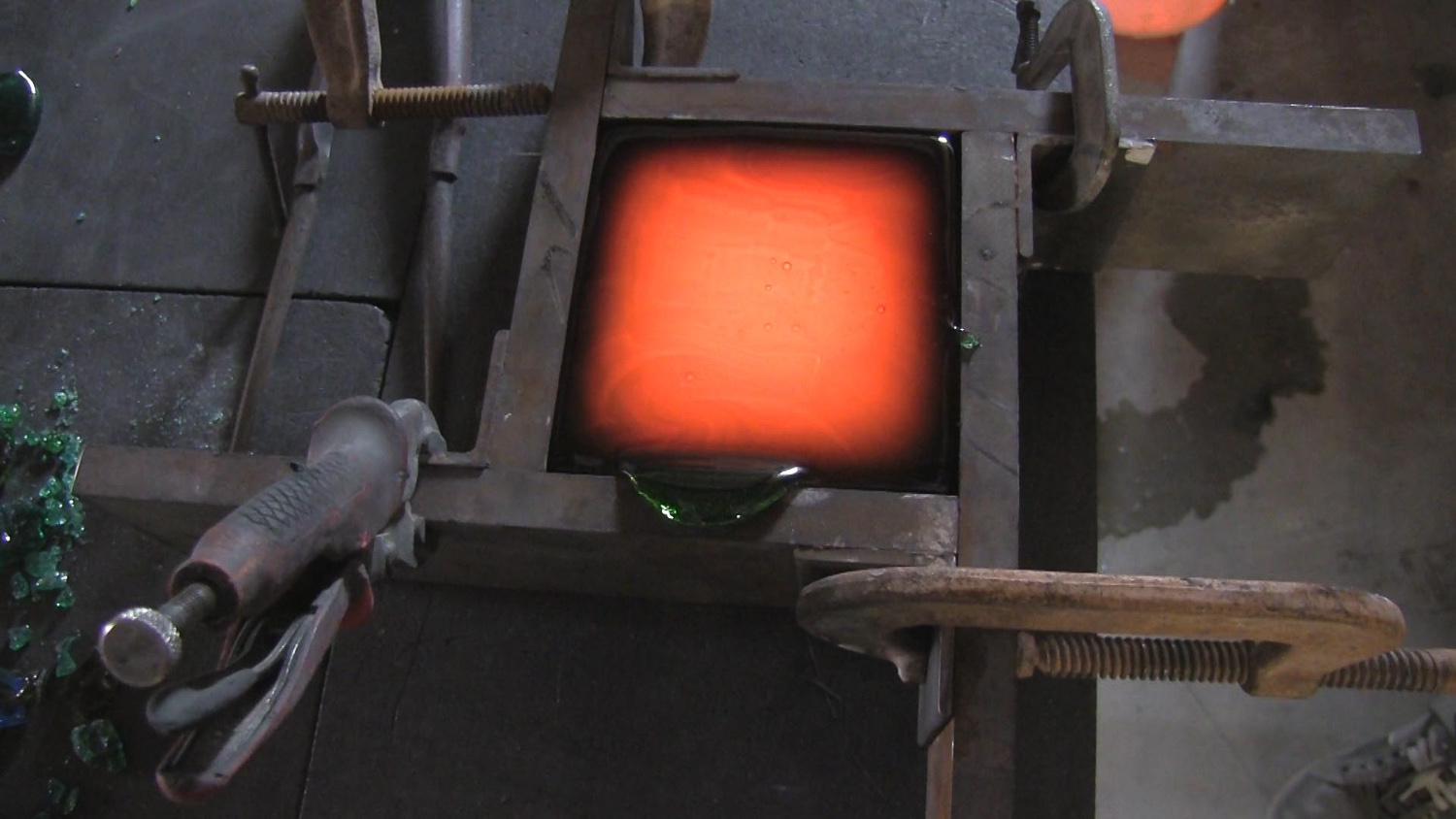

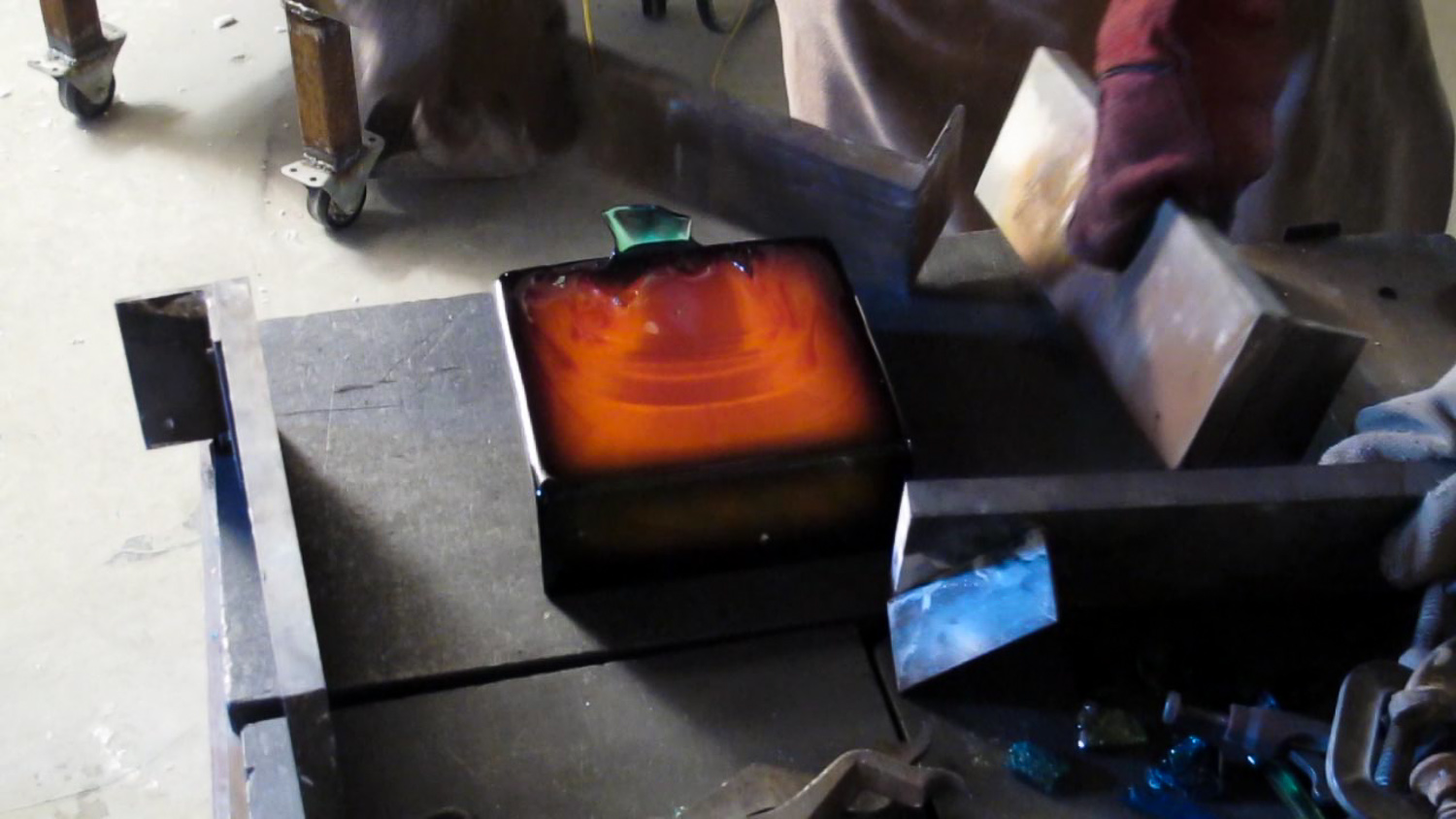

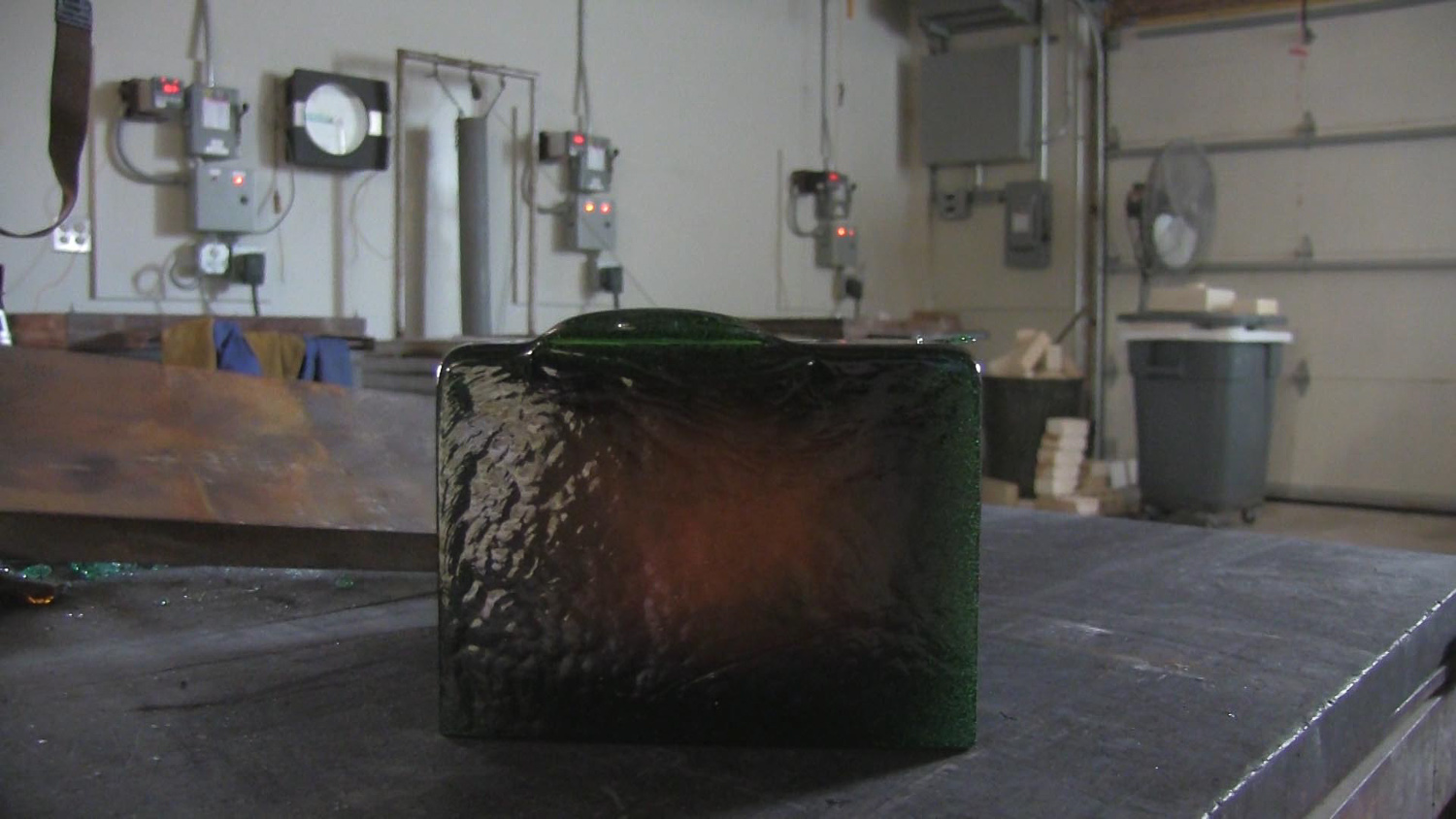

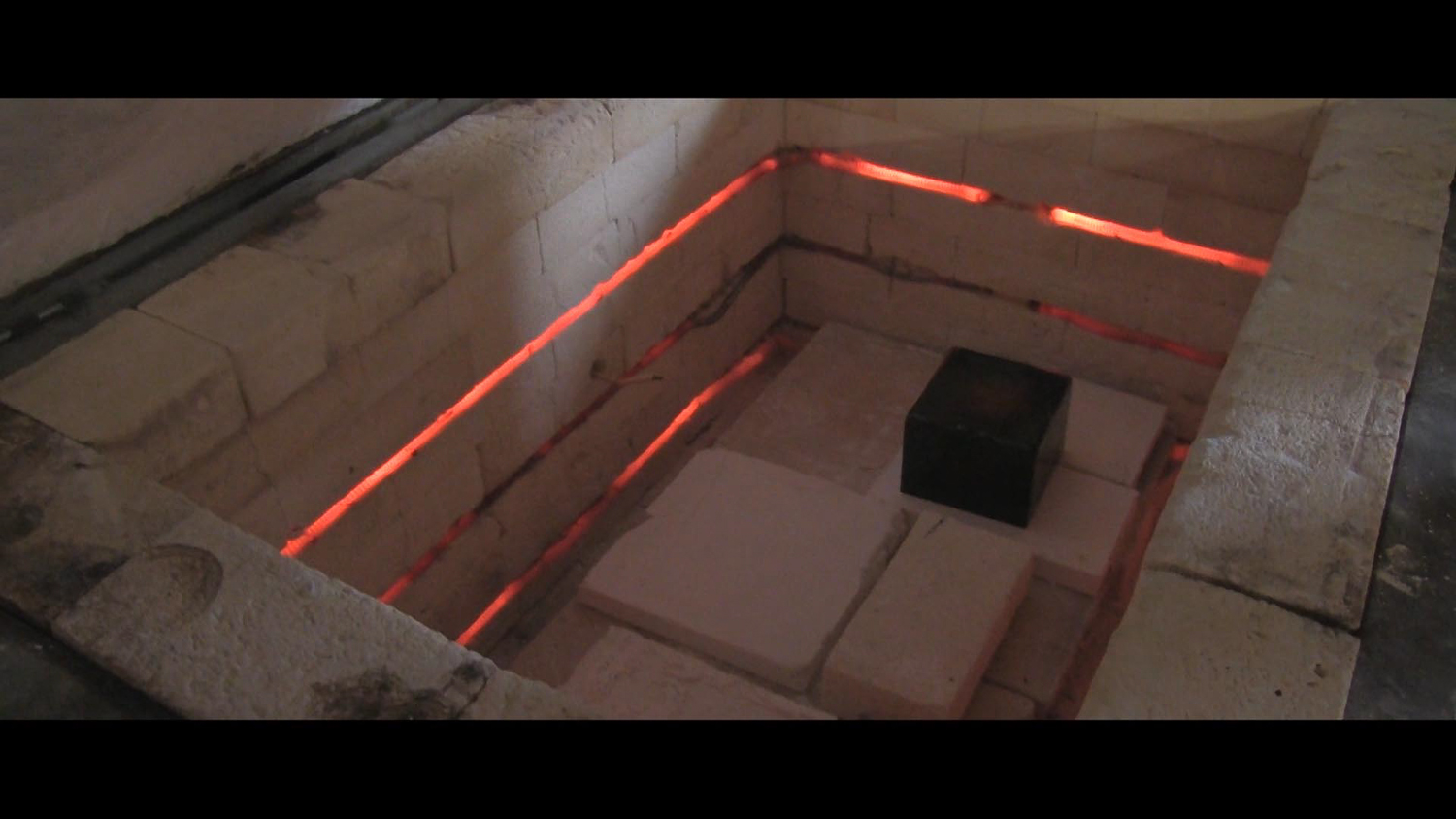

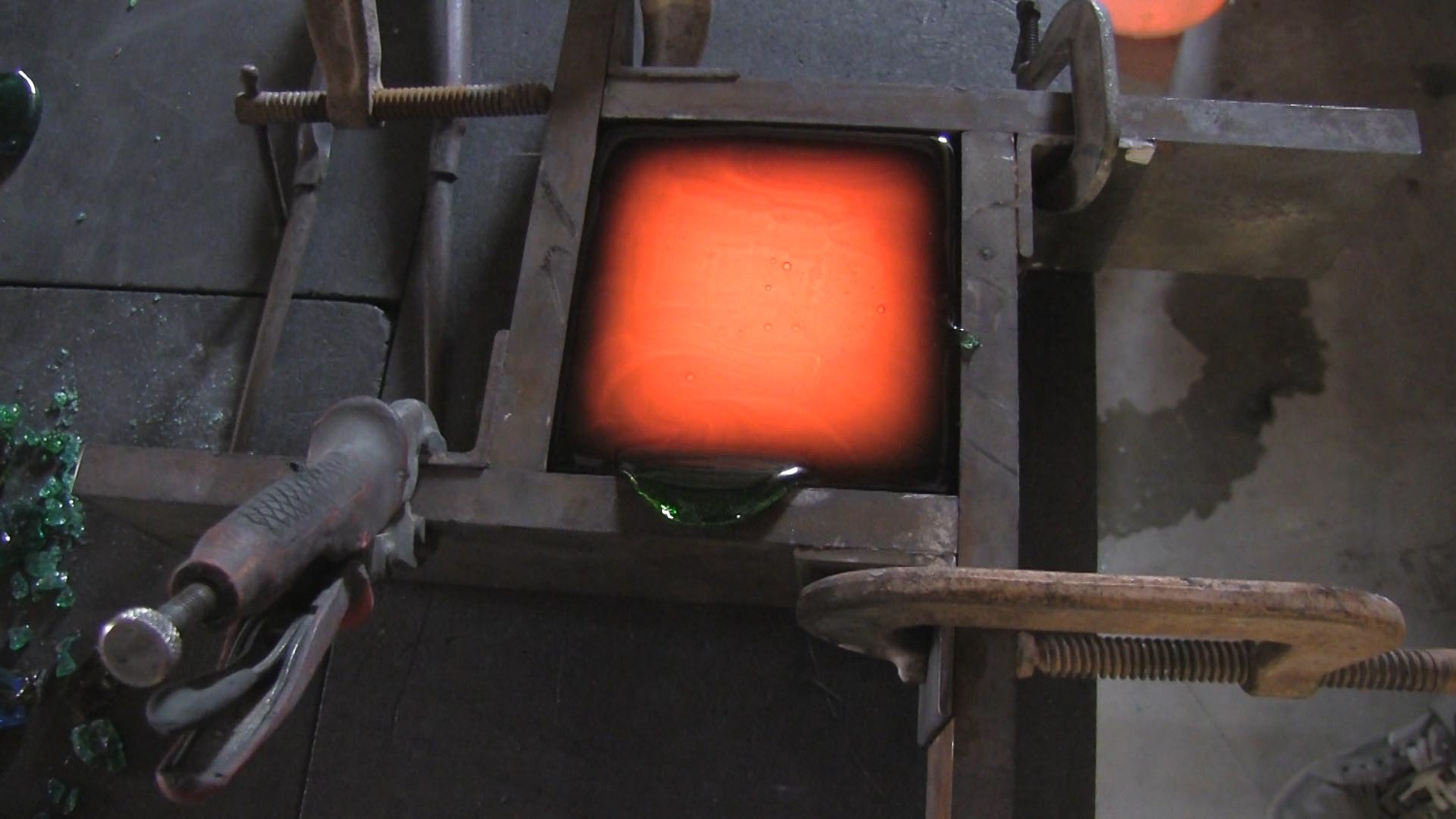

Fire and Glass

Fire

Fire and Glass

Fire

Making Color

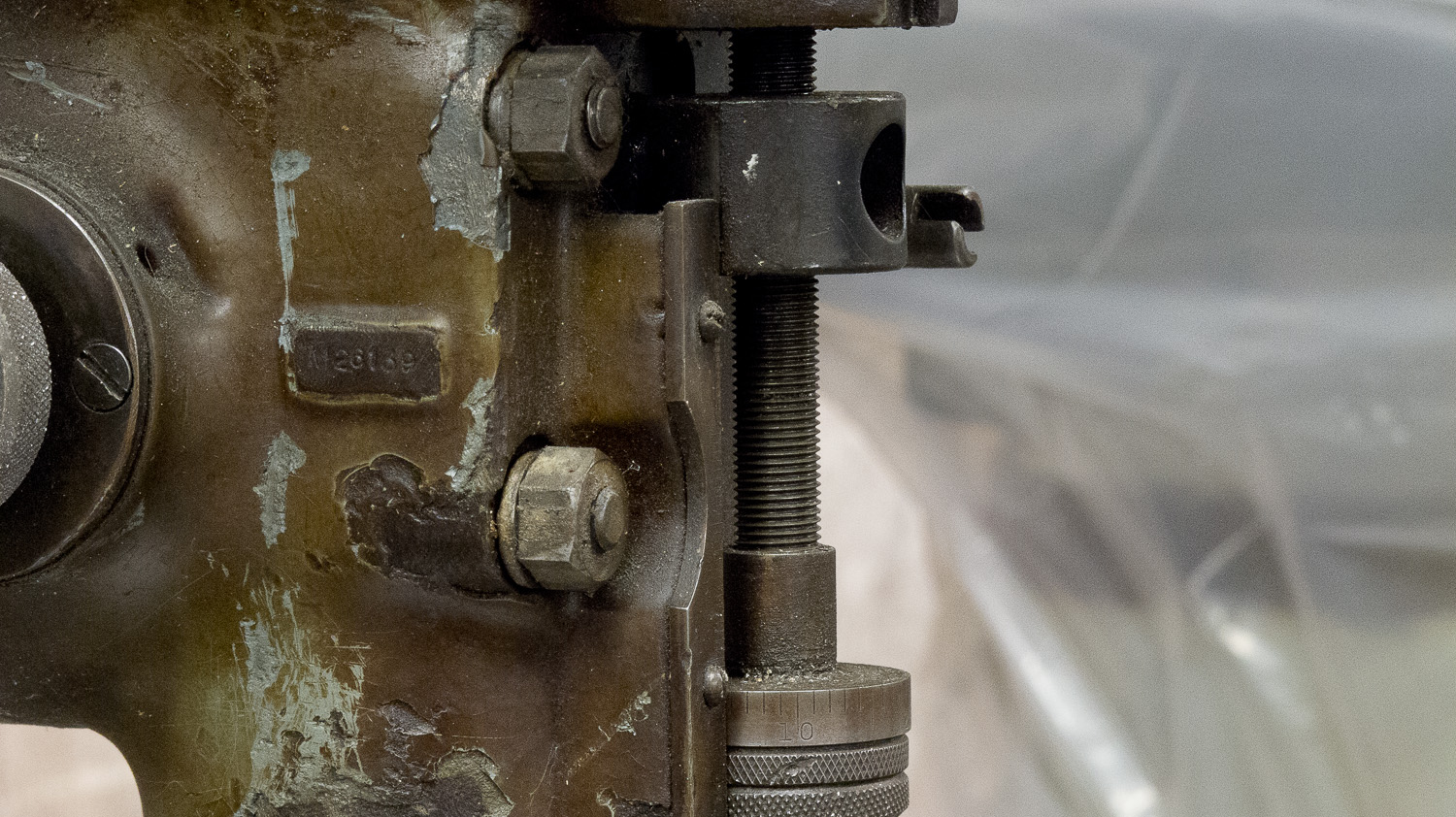

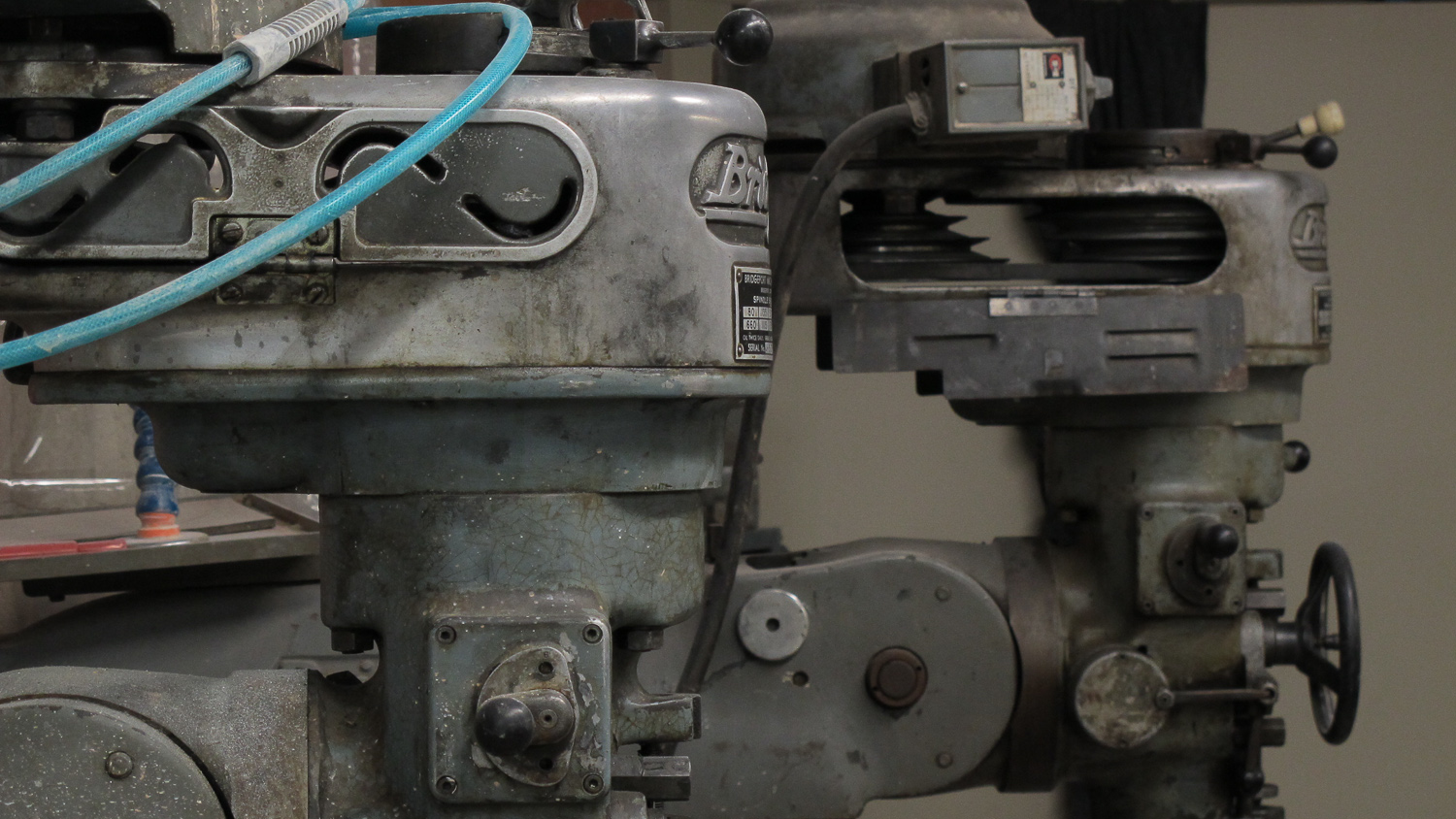

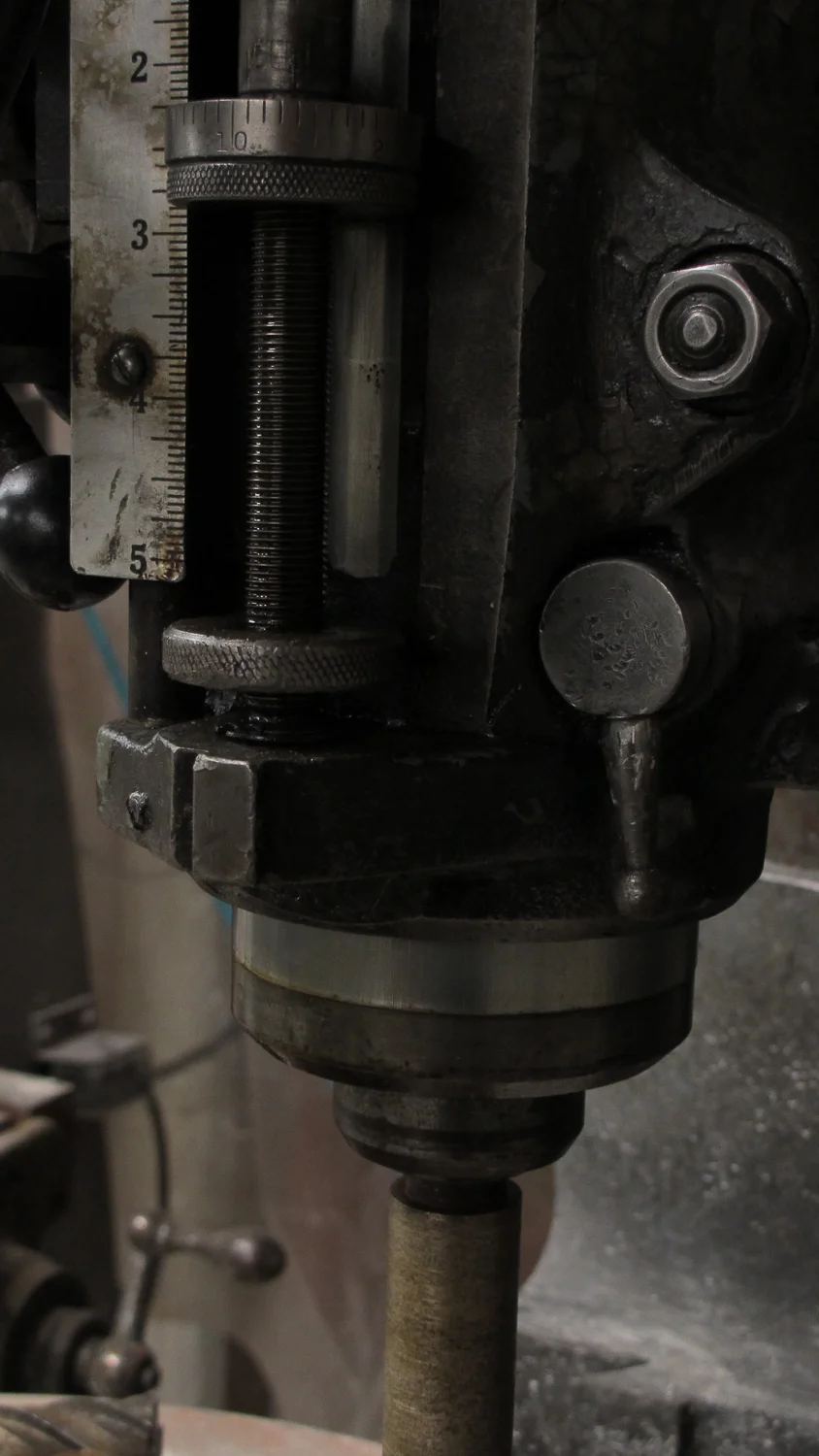

Machines

Machines

Machines

Machines

“We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us”